Gorillaz and the Significance of Artistic Collaboration

Gorillaz, Brixton Academy, London. Photo by Drew de F Fawkes

The first real memory I have attached to music is picking out a “Plastic Beach” CD for my mum to get me when I was 5. I didn’t know anything about them, but I liked the case art. The model of the red island jutting out the dark, foreboding looking water was striking, and for my child brain that was clearly enough to choose it. As I grew up and my taste in music changed, Gorillaz were there in some form for many of the points that stand out in my memory. Rather embarrassingly, “Clint Eastwood” was one of my first times listening to hip hop of any form, as I had limited opportunity to be exposed to rap, growing up in suburban Cape Town. Gorillaz provided an avenue of hearing music that I might otherwise have not been introduced to, at least not at such a young age.

As I started getting “into” music (whatever that means to you), I learned that Gorillaz, while obviously being very popular, were also very well liked by people who talk about music on the internet. This is, as many know, a relatively rare combination, and what's more Gorillaz seemed entirely separate from the weird pretentiousness surrounding listeners of popular, as well as critically acclaimed bands like Radiohead or The Smiths. Rather there was an earnest and sincere enjoyment of their work from fans, who weren’t ashamed to admit that they liked popular songs like “Feel Good Inc” or “Dare”. Seeing the way they were being discussed prompted me to listen to “Plastic Beach” for the first time since I was very young, and I was surprised to enjoy it even more than the first time I heard it. Actually knowing who the features were made me appreciate how genuinely cool it was that these collaborations even happened. What other band could produce an album with features from Mos Deff, Mark E Smith and Lou Reed? Even beyond that, the album just sounds great, switching between so many genres without any jarring tonal shifts, and despite being fifteen years old now, doesn’t feel dated at all.

An obvious reason for the enduring popularity of Gorillaz is the art. Jamie Hewlett’s images provide another avenue to capture attention, simply by looking as distinct as it does. The art in my “Plastic Beach” CD struck me then, and still does now. The style and look of the characters evolved over time, in step with the style and sound of the music changing too. Much of the art contains references to real world cultural artifacts, be it Peter Lorre or Raëlism. This leads me to what I would argue is another cause for Gorillaz still being relevant - the genuine appreciation of other’s art.

Gorillaz is obviously inherently a collaborative project, being created by Damon Albarn and Jamie Hewlett, but really, the band acts as a vehicle for what they're currently enjoying. Each collaboration and feature is an open admission of them deeply adoring another artist's work, enough so to ask that artist to work with them. Gorillaz are not ashamed to show their influences, and want to share them, want others to experience that artists work. Like I said earlier, through their collaboration, and under the guise of pop music, Gorillaz allow their audience to be exposed to a wide range of genres that they might otherwise never have given time to, be it orchestral arrangements or afrobeat. Were it not for this willingness to share the artistic capabilities of these artists, many people wouldn’t have come across them. In a time where a lot of popular music can feel manufactured, such celebration of influence and artistic collaboration is a beautiful, and novel thing.

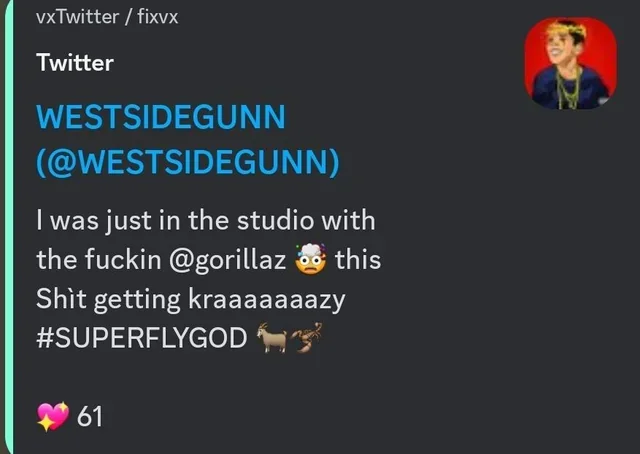

Screenshot of a Discord notification that Westside Gunn had collaborated with Gorillaz.

This tradition of collaboration has led to a Gorillaz feature being viewed as a mark of honour in the industry, particularly in hip-hop. With MF Doom, De La Soul and Bootie Brown of the Pharcyde all having been early guests on Gorillaz tracks, an appearance on a Gorillaz song came to be seen as an unofficial rite of passage for many new rappers. Songs featuring Vince Staples and Little Simz came before major breaks for each in their respective careers, and Westside Gunn, after recording a currently unreleased track released a tweet saying: “I was just in the studio with the fuckin @Gorillaz This shit getting kraaaaaaazy.” A rapper of Westside Gunn’s stature, who had been releasing music for ten years at that point, expressing such excitement at working with Gorillaz shows the reverence they are viewed with in the industry, as well as the large role they play in modern culture. People want to work with Gorillaz, want to collaborate and share ideas with Albarn and Hewlett and create something out of the mutual appreciation of each other's creative output, and that is all thanks to the precedent they've set. Featuring for Gorillaz is mutually beneficial for Albarn, the other artist, and in turn, the audience who are provided a means of hearing an artist they might otherwise not have come across. Gorillaz can be viewed as helping expand the musical palette of a generation.

This all culminates with the exhibition “House of Kong”, created to mark 25 years since the conception of Gorillaz as a band. I went and it’s great, and unlike any other exhibition I’ve been to. Through it all you are constantly reminded of the commitment to detail and care to ensure this group feels “real”. It doesn’t feel like something any other band could do. After reaching the end, you are faced with a mural picturing every single person Gorillaz has worked with over the last 25 years. It feels fitting that the last thing you see at the exhibition celebrating the band's quarter of a century existence, is a monument to artistic collaboration, an acknowledgement that all you have seen over the last hour, and everything that they've done in those 25 years, has only been made possible by this willingness to work and share ideas with others, in the hopes of creating something worth showing to the world.